This post comes from the Artists and Climate Change Blog

October 8, 2016. As soon as I exited the garage across the street from the theatre, the rain pelted the windshield much more quickly than the wipers could whisk it away. The neighborhood was as black as my rented Nissan Altima. The power had gone out and my headlights barely pierced the darkness. The tail end of Hurricane Matthew, originally slated to bypass Norfolk, Virginia, was bearing down. My friend Martha had given me explicit directions to avoid flooding. I tried to get to 26th Street, but at 38th a huge puddle loomed in front of me. I took a chance and made it to the other side. 26th was relatively smooth sailing. Thank you, Martha. I turned right onto Granby. Huge mistake. At the intersection of 21st a small white car was up to its windows in water. Trying to remain calm, I backed up and eventually got back on Granby further south. At Princess Anne, a swirling pond was blocking the intersection. I couldn’t tell how deep it was. Should I go for it? “Well,†I thought. “The car’s a rental and it’s insured.†I held my breath as I put my foot on the accelerator.

July 4, 1933. Bathing beauty Rosa LaDarieux climbed to the top of a flagpole, some fifty-five feet in the air above the Ocean View Amusement Park in Norfolk. From a thirty-inch-square platform, she greeted a crowd of well-wishers gathered below and, aiming to set a flagpole-sitting record, announced her plan to remain on her perch above the Chesapeake Bay beachfront until Labor Day. About two weeks shy of her goal, it started to rain and the wind began to pick up. Little did she know these were the portents of a deadly hurricane that would soon bear down on her—and force her to decide whether or not to abandon her Depression-era stunt.

I first visited Ocean View in the summer of 2013, not to go to the beach or the amusement park (which was long gone), but to do research at the Pretlow branch of the Norfolk Public Library. The city’s historical archives happened to be located pretty much directly across the road from where Rosa LaDarieux “sat†exactly eighty summers earlier. I had been commissioned by Virginia Stage Company to write an original musical, which I eventually titled The Rising Sea, about sea level rise and wanted to learn a bit about Norfolk history.

Norfolk’s a city whose charm is, safe to say, largely derived from its proximity to the water. Rivers and streams flow throughout and the Chesapeake Bay forms its northern border. But an inevitable rise in sea level, caused by climate change, has already started to transform the charm into an ever more constant threat. The area is subject to frequent and severe flooding. Chris Hanna, the Stage Company’s artistic director at the time, suspected that Norfolk residents, inundated by a flood of facts, were becoming inured to this all-important issue. Perhaps turning facts into art would stimulate discussion across large swaths of the community. My assignment was to create a musical that would address the topic but not necessarily in a literal way.

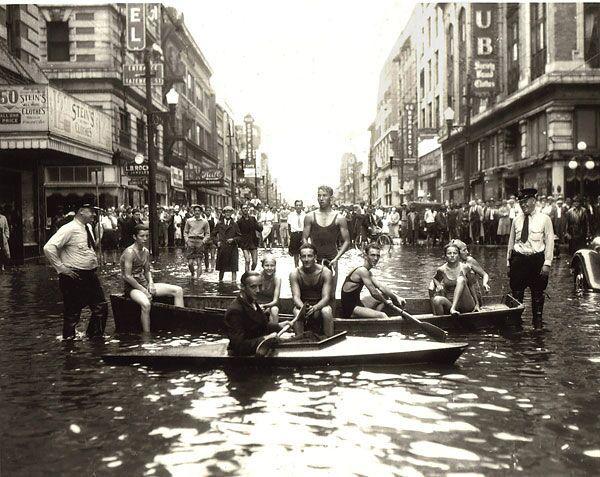

I read a lot of journal articles and met with climate scientists, many of whom were forecasting not only disastrous flooding but also the destruction of the fragile coastline and ecosystems of the Chesapeake Bay. My interest in history led me to wonder when, if at all, Norfolk might have previously been under water. A Google search quickly summoned images of the “Storm of ’33,†a deadly hurricane that flooded downtown.

Searching a bit further revealed the story of Rosa LaDarieux. I’d never heard of flagpole-sitting, which seemed inherently theatrical.

My research revealed that in the 1920s and ’30s, Ocean View was a successful resort on the shore of the Chesapeake Bay, eight miles from downtown. Its gigantic roller coaster and other “amusements†made it a popular destination for locals as well as tourists from up and down the East Coast. It was also segregated. Blacks couldn’t swim there; but they could work as cooks and “domestics†in the whites-only hotels, and as boatmen who rowed whites out on the bay for an afternoon of fishing for spot and croaker.

Many rolls of microfiche later, I returned to New York. I couldn’t get Rosa, the flagpole sitter, out of my mind. And I couldn’t get segregation out of my mind, either. But how could I relate these to climate change? Then I read a New Yorker article in which a scientist described climate change as “the kind of issue where something looked extremely difficult, and not worth it, and then people changed their minds.†He went on to say, “Slavery had some of those characteristics a hundred and fifty years ago. Some people thought it was wrong, and they made their arguments, and they didn’t carry the day. And then something happened and all of sudden it was wrong and we didn’t do it anymore.â€

In my mind, ending slavery—and its legacy of segregation and discrimination—and combatting climate change became inextricably linked. If, as a nation, we could commit to one, we could, and would have to, commit to the other. Within a few hours of reading the article, I invented my central character, a black boy named Granby whose aunt works as a cook at one of the Ocean View hotels during the summer of 1933. She finds him a job running errands for the flagpole sitter (who is white). These include bringing her all her meals, as well as an occasional snack from Doumar’s (where the ice cream cone was invented). Over the summer, Granby and Rosa forge a rather unlikely friendship. Granby is fascinated by the fish and other aquatic life that inhabit the Lafayette River, near his house in Huntersville. Rosa encourages him to study hard in school so that he can eventually turn his love of these creatures into a scholarly vocation. He becomes a marine biologist and ultimately a climate-change activist who sees his precious Chesapeake Bay marine life being threatened by the rising sea. In the musical, we see him as he ages from eleven to ninety. (The role is actually split between two actors.) In a full-circle moment, in the 1970s, he ends up purchasing land and building a house at Ocean View. He can swim in the Bay whenever he wants—something he was forbidden to do as a young man. Progress.

Rising seas are problematic for not only Norfolk but many other East Coast communities (and numerous other locations around the globe). Having lived through a week-long power outage in New York City caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, I was well attuned to how much damage flooding can cause—and it’s only going to get worse. Norfolk is just the tip of the iceberg. And speaking of icebergs, Antarctica is really the origin of sea level rise. What happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica. If increasing global temperatures cause ice to melt there, much of that extra water is going to head up toward the eastern seaboard of the USA. I decided to set half the story in Antarctica in the year 2047.

Two climate scientists—Granby Jr., an African American (named for his great-grandfather), and Misaki, a Japanese American—happen to meet in an especially remote area of this strikingly beautiful continent. Both are researching the quickly melting ice. Many parts of the East Coast are becoming uninhabitable, and Granby Jr. learns his great-grandfather’s house at Ocean View has just been swallowed up by the rising seas. He attempts to process that loss, and as Misaki helps him do so, they discover their pasts are linked in surprising ways. After a contentious courtship, they fall in love. Their interracial relationship would have been a felony in the Virginia of Granby Jr.’s great-grandfather. Progress.

The musical’s two interconnected stories, one set in the northern hemisphere and one in the southern, one set in the past and one in the future, appear in alternating scenes. The past and the future are intimately connected, just as all of us are connected by the currents of the oceans and the changing climates they convey. The characters’ links across continents and time reinforce the idea that the solution to climate change must be a global one.

***

Tavon Olds-Sample, a sixteen-year-old native of Norfolk, played the role of the younger Granby. When he read the script, he was excited about the opportunity to inhabit the body and get inside the head of a boy around his age from the Norfolk of the 1930s.

History became present for Tavon, the rest of the actors and me when, at one of the audience talkbacks, a black woman in her seventies who grew up in the Titustown section of Norfolk shared her memories of segregation. “I went to Grant’s and Woolworth’s, to the lunch counters and sit-ins,†she told us. And she made a point of saying that even though she could now buy an ice cream cone at Doumar’s, she would never do so—on principle. When she was a child, they wouldn’t serve blacks.

The musical also made Tavon aware that to counter the rising seas, we are going to have to build “resilient†cities, with houses and infrastructure that float. “Sea level rise wasn’t something I’d thought about. Playing the character changed how I look at the world.†I think it’s safe to say it did the same for audience members, one of whom acknowledged that “if the human race is going to survive, we have to fight against climate change just as fiercely as we fought for civil rights.†As one environmental advocate has summed it up, “We are at our lunch counter moment for the twenty-first century.â€

***

Hurricane Matthew decided to visit Norfolk for our last weekend of performances. The weather that Saturday deteriorated quickly. As I drove to the theatre for the matinee, the rain was already falling steadily. At a red light, I checked the Doppler. Several ominous-looking yellow and orange bands were headed our way. After the show, audience members didn’t linger in the lobby to debate the musical’s merits. Their priority was getting back home.

Those of us involved with the production remained at the theatre and had a bite to eat. It was still pouring when a handful of diehard audience members arrived for the evening performance. Ten minutes into the show, Granby (Tavon) was delivering ice cream to Rosa, who was up on her flagpole. He was about to warn her about a coming storm when the spot lights flickered. Except this wasn’t a lighting cue. The power in the theatre was failing. The emergency lighting came on. The stage manager’s forcefully announced “Hold!†reverberated through the auditorium. The actors were instructed to leave the stage and the audience sat quietly for a few minutes. The producers hastily concluded the weather had deteriorated to such a degree that the priority was making sure everyone could make it home as quickly as possible. The stage manager announced the performance’s cancellation. Cast and crew dispersed.

I left for the garage and was not remotely anticipating that difficult journey back to my apartment. At the intersection of Granby and Princess Anne, I drove slowly though the whirlpool without trashing the rental car. The rest of the trip, which took a total of an hour instead of the usual fifteen minutes, was relatively smooth sailing. Pun intended.

I lay awake most of the night, holding on to the slim hope the show would go on the next afternoon. It was to be our closing performance. I woke up early Sunday morning to the news that the state of emergency declared by the City of Norfolk the night before was still in effect. The matinee would be cancelled.

I counted my blessings and tried to be resilient. I had made it back safely. Down in North Carolina, the storm had caused a lot of damage. The images were distressing and my heart went out to those who lost their homes. I thought about Ocean View in 1933. The winds had forced Rosa LaDarieux to abandon her perch. Lucky for her she did, because the flagpole eventually snapped. But how reluctant she must have been to descend, just two weeks shy of her record; how angry and disappointed she must have felt. How angry and disappointed I felt. There would be no chance to say a proper, teary farewell to the cast with whom I’d worked so hard. No chance to watch the crew dismantle the set that had been home for the past couple of months. Hurricane Matthew had deprived us of our final performance, just like the Storm of ’33, decades before, had deprived Rosa of hers. Life imitating art imitating life.

Eric Schorr’s musical The Rising Sea (originally titled, I Sing the Rising Sea) had its world premiere at Virginia Stage Company in 2016. Funding for the production was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ensemble Studio Theatre/Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Science & Technology Project.

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.