By tanjabeer

This interview is the first of a series of interviews that I am conducting with eco-theatre professionals over the next couple of months. Thierry Leonardi has been working for culture for the last 25 years. He has been the Lyon Opera Ballet General Manager from 1995 to 2015 and the sustainability officer of the Lyon Opera from 2008 to 2015. Since 2016 he has worked as a CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) consultant with cultural organisations, helping them to formalize and implement their sustainability strategies and road maps. He is a member of the labelling committee of French CSR label Lucie26000.

How did your interest in theatre and sustainable production begin?

In 2008, I was working as the general manager of the Lyon Opera’s ballet company when I was invited to join an internal working group on sustainability. Believe it or not, I never heard of sustainability beforehand. All these issues and stakes connected to one another made so much sense and were deeply challenging our routine. They were really opening up new horizons.

What does sustainability mean to you? How do you define it (for yourself and others)?

Sustainability is an evolving concept. It has challenged the economy for the last twenty years through the concept of corporate social responsibility. In other words, economic activities only make sense if they prove to be socially useful – if they contribute to a more inclusive and ethical society. A favourable climate, a well-preserved (and possibly restored) biodiverse environment and resource availability are all prerequisites for such a society. Instead of understanding sustainability as the intersection of three circles (economy, social & environment), I prefer to represent it as the inclusion of these circles, from economy (the smallest one) to environment. Lastly, I think it is clear for most of us that sustainable development is a cultural issue. We need to rethink our values to forge new narratives, among which frugality will probably be a major one. This creates a fourth circle and I would represent it as the bigger one, as culture (in its anthropological sense) has an impact on nature. On a more personal level, frugality would probably be the best word to translate sustainability, but I am still far from it!

Can you tell me about some of your recent work on the OSCaR project? How is it proposing a new approachto Opera production?

OSCaR was born from the conviction that the Opera industry needs collective action and capacity building to make substantial progress in eco-design, and that Europe is in a strong position to produce significant results in this area. OSCaR is the very first step in a long journey towards circular economy in the Opera industry that focuses on the lifecycle of set design, manufacturing and management. It includes seven partners and is co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union. The project includes finalising a state-of-the-art review of (eco) set design practices in European Opera Houses, which should be published in the first quarter of 2021. It will also include an exploration of the management processes involved in the lifecycles of opera sets. The outcomes of these two inquiries will be shared with the technical (and production) departments of European Opera Houses. Hopefully we will be able to set up more collaboration opportunities to deepen the research and development on a few specific topics.

Can you tell me about the EDEOS tool? How does it work in practice? What are you hoping to achieve with the tool and how does it compare with other tools such as the Julies Bicycle IG tool?

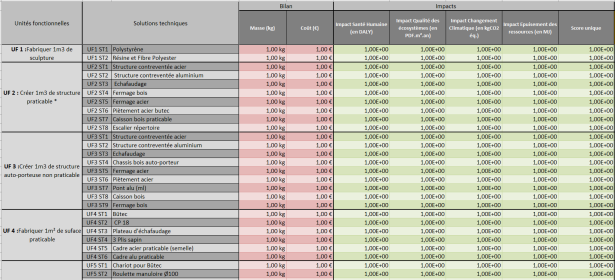

While OSCaR is a collective circular economy exploration project with eco-innovation at the core of its vision, EDEOS is an eco-design tool that has been developed by the Lyon Opera for its own needs, the first version of which has already been operational for one year. Both initiatives contribute to the same quest from two different perspectives. EDEOS is a footprint calculator for stage sets which assesses four categories of potential damages, including: climate, human health, ecosystems and non-renewable resources. Based on manufacturing scenarios, calculations are made during the set design concept phase, which makes EDEOS a real decision-making tool. As well as calculating the footprint of set designs, EDEOS also measures key indicators of eco-design, such as the percentage of reused or recycled elements used in scenic manufacturing. Eco-design indicator values are calculated before the set is constructed, as well as considering what happens to the sets afterwards based on manufacturing scenarios. This includes identifying the impact of construction methods on the quality of materials.

The present version of EDEOS consists in two Excel spreadsheets: one calculator and a database. The database includes all the supplies and technical solutions that are referenced by the set workshop of the Lyon Opera. The impact values associated with the supplies are calculated through a lifecycle analysis (LCA). The implemented lifecycle analysis methodology (LCA) is called IMPACT 2002+, and the database used for impact calculations is called Ecoinvent. They are both extensively used by LCA experts. So far, half of the supplies referenced by the Lyon Opera workshops have gone through an LCA process and our first task is to complete the database.

As I said above, EDEOS is a decision-making tool. Its purpose is not to have a very precise value of a set design footprint but to improve eco-design practices by making better informed decisions. I don’t know comparable tools in the French cultural industry, nor abroad actually, but I could have missed something. By ‘comparable’ I mean, a decision-making tool that is more than a carbon calculator. Julie’s Bicycle IG tool is an auto-assessment tool of a cultural organisation’s environmental policy, on three stages of its implementation: commitment, understanding and improvement. Its purpose is different than EDEOS.

What has been the industry’s response to the tool so far? Has the response been positive or have you also been met with resistance?

To date, EDEOS has only been used by the Lyon Opera and has been designed to answer the needs of that organisation, with a database that includes its own supplies and impact data. Nevertheless, EDEOS could provide a good foundation for a shared industry tool, which could also include cinema and exhibitions. We have already introduced EDEOS to different communities in France and abroad and so far, they have shown a real interest. We are still in the process of presenting the tool to get more feedback, and are planning to test it with a few opera houses during the first half of 2021. This testing phase requires an appropriate organisation, because just leaving EDEOS in the hands of other users might be counterproductive.

In her speech at World Stage Design in 2013, eco-arts scholar Wallace Heim argued that the time will soon come when theatres will need to justify excessive and unsustainable behaviour – when ‘those who want massive spectacles, world tours, and blazing lights will have to openly justify and account for those technologies and excessive and exceptional drains’ (2013). What do you think about this argument? Do you think carbon budgets will be an inevitable part of our future? How have you seen carbon budgets used in your work? Can you give an example?

I think she is right. When I started to work on sustainability at the Lyon Opera about 10 years ago, I thought that within 10 years the French Ministry of Culture and local governments would include sustainability criteria in their funding decisions. We are not quite there yet but things are speeding up. Something is interesting about this speeding up: industry professionals are asking for it, including small companies. The impact of touring is really questioned now and when you talk about touring, you are talking about your business model, which makes sustainability finally strategic. It is the same with private sponsorship, which is also financially crucial for certain organisations and is ever more challenged by ethical questions. I don’t mean that we should totally waiver the option of touring, but probably reduce it and learn how to do it differently. Once again, for me it is about shifting from excess to moderation or frugality. I guess that at some point audiences themselves will ask for accountability. So, specifically, I think that we will come to having environmental budgets (whether strictly carbon or not) in assessing our projects and making decisions, just like we do with money. I believe that resource wise we’ll have to do with less, so we will need to set limits in absolute values. I have not seen such budgets in the cultural industry so far, which is consistent with its slow adoption of sustainability, but I couldn’t say that nobody has done it yet.

What do you think the future of theatre will look like for a climate-resilient world?

Being an absolute necessity, frugality might become a cardinal value of our future societies. I would not be surprised if these societies also develop an aesthetics of moderation. Artworks will probably address more extensively impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss etc., if only through the social, economic, political and geopolitical consequences of these changes. If I am more specific, I guess there will be less excessive productions and touring of theatre, cinema and exhibitions. In other words, the lifecycle of productions will slow down, like our own lives maybe. Our relationship to art/theatre/cinema works will also change, and hopefully we will not be mere ‘cultural goods consumers’ anymore.

The post, Opera production & the circular economy: interview with Thierry Leonardi (Lyon Opera), appeared first on Ecoscenography.

———-

Ecoscenography.com has been instigated by designer Tanja Beer – a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, Australia, investigating the application of ecological design principles to theatre.

Tanja Beer is a researcher and practitioner in ecological design for performance and the creator of The Living Stage – an ecoscenographic work that combines stage design, permaculture and community engagement to create recyclable, biodegradable and edible performance spaces. Tanja has more than 15 years professional experience, including creating over 50 designs for a variety of theatre companies and festivals in Australia (Sydney Opera House, Melbourne International Arts Festival, Queensland Theatre Company, Melbourne Theatre Company, Arts Centre) and overseas (including projects in Vienna, London, Cardiff and Tokyo).

Since 2011, Tanja has been investigating sustainable practices in the theatre. International projects have included a 2011 Asialink Residency (Australia Council for the Arts) with the Tokyo Institute of Technology and a residency with the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama (London) funded by a Norman Macgeorge Scholarship from the University of Melbourne. In 2013, Tanja worked as “activist-in-residence†at Julie’s Bicycle (London), and featured her work at the 2013 World Stage Design Congress (Cardiff)

Tanja has a Masters in Stage Design (KUG, Austria), a Graduate Diploma in Performance Making (VCA, Australia) and is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne where she also teaches subjects in Design Research, Scenography and Climate Change. A passionate teacher and facilitator, Tanja has been invited as a guest lecturer and speaker at performing arts schools and events in Australia, Canada, the USA and UK. Her design work has been featured in The Age and The Guardian and can be viewed at www.tanjabeer.com

Powered by WPeMatico