By Amy Brady

Meet Amy Howden-Chapman and Abby Cunnane, two artists who founded and edit The Distance Plan, a journal that includes art, essays, and experimental writing on climate change. The journal is an offshoot of The Distance Plan organization, a collective of artists and writers who produce exhibitions and participate in public forums on climate. In the Q&A below, we discuss what inspired them to launch the journal and what they hope readers will take away from it. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

The Distance Plan journal is published by the Distance Plan organization, which is a collective of artists, writers, and activists. Can you describe your organization’s mission and the type of work you create and promote?

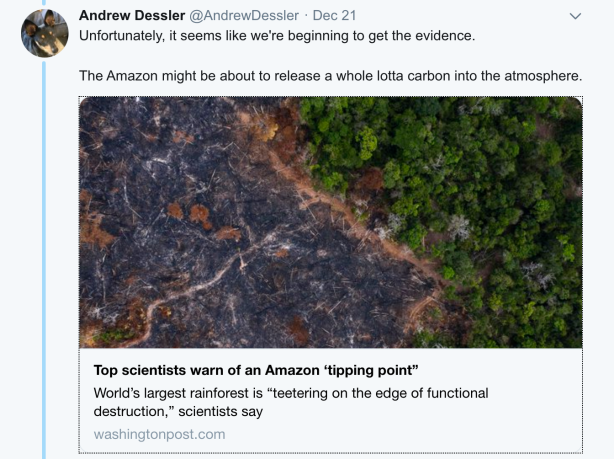

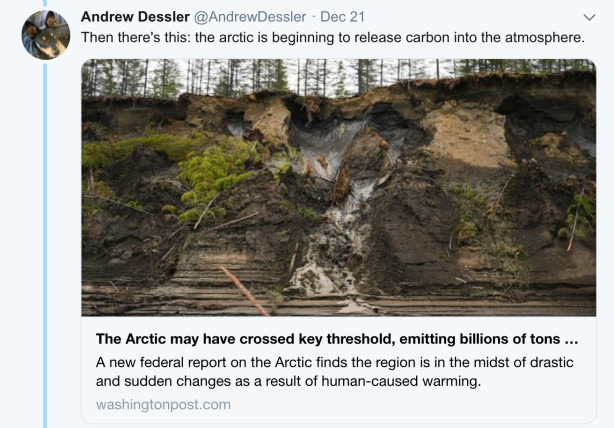

We founded The Distance Plan in 2011 because we felt that discussion about climate change wasn’t happening in humanities contexts that we knew. While there were people working on the issue in various fields, especially in the sciences, we wanted to bring them together with artists, activists, and writers, and to provide a platform that would present these interdisciplinary conversations to a broader audience. Today a lot of people understand that the response to the climate crisis will require a mobilization in the arts; we need to represent the problems of the past and present and imagine a better future, and telling stories that reflect the diversity of our experience is important in these regards. But back then, knowledge about climate change was relatively siloed within a few academic spheres, and the way this knowledge was communicated to the public involved equally remote images and narratives. All those photographs of polar bears and melting arctic ice!

The journal contains gorgeous poetry and prose about climate change. What do you hope readers take away from each issue?

Our most recent issue, “Charismatic Facts: Climate Change, Poetry and Prose,†focuses on the ways language can be used to circulate powerful pieces of information about the climate crisis (one example, borrowed from David Wallace-Wells, is the fact that humans have emitted more carbon in the last thirty years – since the premiere of Seinfeld – than in all prior history). For other issues, we’ve invited artists and scientists to produce images of local climate impacts: things happening within their various communities. The idea is that this may inspire others to attend to the more immediate effects of climate change while also acknowledging the global scale of the problem. The hope is that readers will take away an anecdote, image, or feeling – something that relates to their own sphere of life and work and enables them to imagine possibilities for climate action within their own practices and political endeavors. We want people to get involved.

The “Lexicon†is a project you are exploring both in print and in your exhibitions. What is the “Lexicon†and how did it come about?

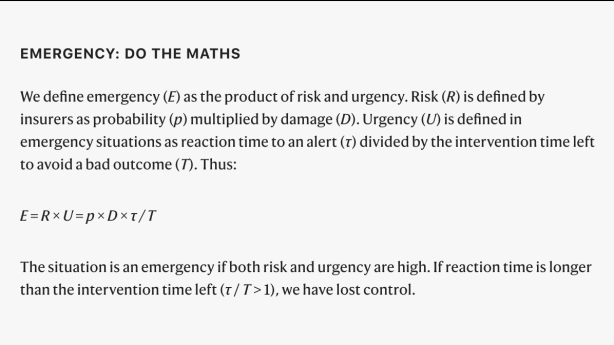

The Distance Plan “Lexicon†is a collaborative glossary of terms (each accompanied by an image) that describe aspects of the climate crisis, providing language through which we can address problems or giving names to under-represented categories of experience. One example is “Gendered Climate Impacts,†a Lexicon term that refers to the way global warming affects women and non-binary folk differently from others, often with disproportionately negative outcomes. Another term is “Real-Time Attribution,†which is a relatively recent phenomenon within climate science wherein extreme weather events are now being linked to anthropogenic warming, even as they are happening.

Why are narrative and artistic responses to climate change important?

Climate change is a cultural problem as much as it is an economic, scientific, and political one. We need to radically transform our societies and social ideals (at least our contemporary capitalist ones) in order to meet this challenge. Historically, art – and especially storytelling – has played an important role in mobilizing social movements, critiquing wrongdoing, and envisioning positive change. But because the climate crisis is transcultural, the visual arts and other non-verbal forms are increasingly valuable as we seek to activate a global response. It’s wonderful to see Extinction Rebellion using creative modes of performance and a strong graphic-design identity to speak to people around the world.

Large presses have given us several novels and poetry collections about climate change in the last couple of years. But what kind of freedoms does an independent zine allow you? Do you feel that there are ways in which you can discuss climate change in the journal that you may not be able to elsewhere?

Well, to begin with, we’re not subject to the constraints of a for-profit publishing model. But our independence also means that we can be more nimble and mobile when it comes to what we do and the audiences we engage. The Distance Plan is run between Aotearoa New Zealand (where Abby Cunnane is based) and New York City (where Amy Howden-Chapman now lives). The project has represented the work of contributors from all over the world and we value the ability to turn our attention in each issue to different places and concerns.

What’s next for you both?

We just participated in the Our Futures Festival, which was associated with the UN’s Climate Week, and also hosted a discussion with Janine Randerson, a climate artist and writer, and Albert Refiti, an architect and researcher who studies Pacific spatial and architectural environment. Stay tuned for updates about more Distance Plan events in New York. And we’re working on the next print issue. Sign up for our newsletter to stay informed about everything and to receive our next call for submissions.

How can my readers get copies of the journal?

Within the US and Europe the journal is available for purchase directly through our website. If you’re in New York City, you can find the latest issue at Printed Matter. There are a number of bookstores in New Zealand that stock our issue and they are listed at TheDistancePlan.org.

(Top image: The “Lexicon†on view at an art festival on Governor’s Island.)

This article is part of the Climate Art Interviews series. It was originally published in Amy Brady’s “Burning Worlds†newsletter. Subscribe to get Amy’s newsletter delivered straight to your inbox.

___________________________

Amy Brady is the Deputy Publisher of Guernica magazine and Senior Editor of the Chicago Review of Books. Her writing about art, culture, and climate has appeared in the Village Voice, the Los Angeles Times, Pacific Standard, the New Republic, and other places. She is also the editor of the monthly newsletter “Burning Worlds,†which explores how artists and writers are thinking about climate change. She holds a PHD in English and is the recipient of a CLIR/Mellon Library of Congress Fellowship. Read more of her work at AmyBradyWrites.com and follow her on Twitter at @ingredient_x.

———-

Artists and Climate Change is a blog that tracks artistic responses from all disciplines to the problem of climate change. It is both a study about what is being done, and a resource for anyone interested in the subject. Art has the power to reframe the conversation about our environmental crisis so it is inclusive, constructive, and conducive to action. Art can, and should, shape our values and behavior so we are better equipped to face the formidable challenge in front of us.

Go to the Artists and Climate Change Blog

Powered by WPeMatico

The Long Now.

The Long Now. The Long Now.

The Long Now.