This Post Comes from HowlRound:

This week on HowlRound, we continue our exploration of Theatre in the Age of Climate Change with more urgency than ever. With the looming eradication of climate science data from US government websites and the appointment of Scott Pruitt as head of the Environmental Protection Agency, Trump has indicated in no uncertain terms that the health of the planet and its inhabitants are of no concern to him. As theatre artists, how do we respond? Dutch opera director Miranda Lakerveld reflects on the prominence of water imagery in traditional music dramas from the Middle East and on the connection between conflict and ecology. —Chantal Bilodeau

I am writing this article the day before the Dutch elections. Far-right populist Geert Wilders has been leading the polls, and Turkish-Dutch youngsters are marching the streets waving dramatically large Turkish flags. For the first time in my life, I see military police trucks (and water-tanks) drive past my window. CNN and Al Jazeera discuss the “situation” in the Netherlands. Unimaginable things are happening to my country.

I create operas as a platform for dialogue in a multicultural society. My artistic work stems from research on music dramas from around the globe. I was fortunate to be able to do research on a wide range of music- drama practices, for example Tibetan Opera at the Tibetan Institute for Performing Arts; passion play Ta’ziyeh in Iran; and the ancient Maya dance-drama Rabìnal Achi in Guatemala.

Ironically, I found the richest traditions in places where cultural identity is under pressure, especially after a history of violence. For example, one of the first official actions the Dalai Lama took when he arrived in India after fleeing persecution in Tibet, was to establish the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts to preserve Tibetan Opera. We might conclude that these music dramas can be extremely important in times of uncertainty and conflict.

jh Samira Dainan in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie

jh Samira Dainan in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie

“Why does cultural identity create such conflict? And, how does the environment influence the dynamics between cultures?”

While I was doing my research, tensions between communities kept rising at home. Since 2014, my company World Opera Lab has been working mostly in the diverse neighborhoods of Amsterdam-West, applying the aesthetics of music dramas from Iran, India, Tibet, and Middle America to opera. The aim is to create a form of opera that reaches across cultures and artistic traditions.

In these creative dialogues between cultures, I have often wondered: what “makes†a culture? Even in the diaspora, what makes people attached to it? Why does cultural identity create such conflict? And, how does the environment influence the dynamics between cultures?

A series of debate operas on conflict in the Middle East, presented in collaboration with the Debate Center De Balie, has shone a new light on these questions. Why Yemen Matters, created in 2016, deals with the ongoing conflicts in Yemen and why the violence received so little attention in the West. The opera revolves around the story of the Queen of Sheba, who was originally from Yemen. Music from Händel’s oratorium Solomon, played on the Arabic ud and viola da gamba, was countered with traditional songs from Sana’a. The staging was created in dialogue with the work of Yemeni photographer Amira Al-Sharif, who also helped with finding appropriate traditional music. Interestingly, the traditional songs that “floated up†during the work had extensive references to water and its sources:

The leaf of the grape appeared

To collect water, she comes to source: Wadi Bamaa

Passing by me

Passing by me

I, oh my father, I

Glory, oh people, glory to the source, Wadi Amaan

—“Ghuzan Al Qina†(Traditional song from Sana’a, Yemen)

Through these songs, I understood the importance of water sources in the region and how they affect conflicts. The songs also taught me how cultures are very much influenced by the environment. The environment shapes the culture, and consequently it shapes cultural identities.

Samira Dainan and Mireille Bittar in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie.

Samira Dainan and Mireille Bittar in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie.

“The environment shapes the culture, and consequently it shapes cultural identities.”

A River Runs Through It

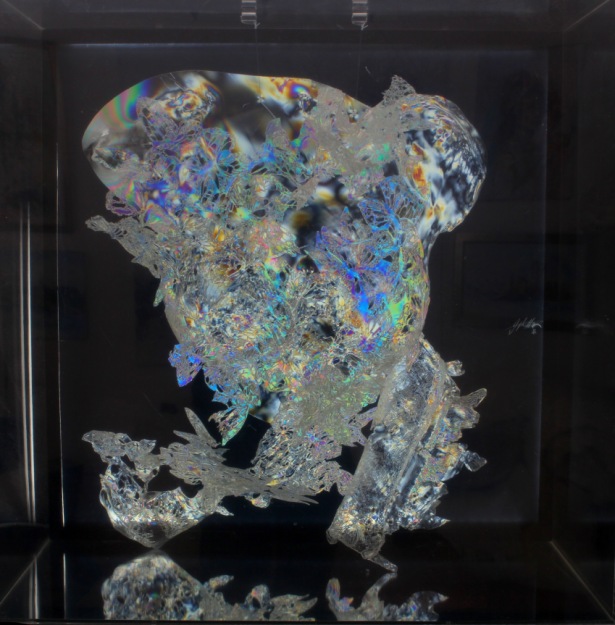

Requiem for a River picks up where Sheba left off. It is a new debate opera that will be presented in the spring of 2018, as part of the on-going collaboration between World Opera Lab and The Middle East Report in the Debate Center De Balie.

The Euphrates River is the main character in this opera, where religious stories about the iconic river are the point of departure. Currently the Tigris and Euphrates, the two main arteries in the Middle East, are rapidly drying up. According to a 2015 article published in Foreign Affairs, the mighty rivers that feed Syria and Iraq may no longer reach the sea by 2040.

The Euphrates, an important “figure†in religious texts, is featured in central stories on conflict in the region as well as in classical operas. After the destruction of Solomon’s Temple, Israelites are brought into exile in Babylonia and sing, mourning their lost homeland at the bank of the river. Psalm 137, in which this scene is depicted, inspired Verdi to write Va pensiero, the famous chorus from Nabucco. According to the Islamic hadith, the Euphrates will dry up and uncover a mountain of gold that will incite bloody conflicts.

In the Ta’ziyeh of Abbas, a Shiite passion play, the Euphrates River is occupied by the Sunni army, while the Shiites are on the losing side. General Abbas goes to the river to get water for the dying children in the camp. After gathering the water, Abbas is attacked and both his arms are amputated. Abbas continues to carry the water bag in his mouth. One arrow hits the bag and water pours out of it. This image of Abbas without arms, and the water sack in his mouth is iconic in the Shiite culture.

According to Iranian scholar Hamid Dabashi, the characters in Ta’ziyeh are metamorphic: “The metamorphic aspect of Ta’ziyeh characters makes them at once extremely potent allegories of cosmic significance, and yet instantaneously accessible to contemporary re-modulations.†In this way, Abbas becomes a potent symbol of the conflicts in the Middle East, drawing our attention to those who are suffering the consequences, and to major underlying themes such as water scarcity and ecological problems. Today in Karbala, Iraq, where this story takes place, farmers are in despair about water shortages.

We learn that water shortages have shaped our civilizations. The very first civilization emerged only when governments where able to provide access to water. Already in ancient times, city-states were cutting off each other’s water supply. And this still goes on today.

In Ta’ziyeh performances, the Euphrates is represented by a large bowl, in which the audience is invited to empty their water bottles. Stagehands then fill up the bottles with water from the bowl, and give them back to the audience. This water is now considered sacred and wholesome. This scene has an important lesson for us: it connects religious conflicts and cultural identity to ecology.

Ta’ziyeh of Abbas in Ziaran, Iran 2012. Photo by Miranda Lakerveld.

Ta’ziyeh of Abbas in Ziaran, Iran 2012. Photo by Miranda Lakerveld.

The River Reaches the Sea

I am editing this article a few weeks after the elections. For now, The Netherlands seems to have dodged the populist bullet and the eyes of the world are now on France’s elections. Spring has started, and the country is relieved. At the same time, the conflicts in the Middle East are erupting with renewed violence.

I am reading poetry from Iraq, and I am reminded again of how many water sources are shared across cultures. The Euphrates is the river that shaped the first civilizations. She runs through all of us. Or in the words of the Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab:

…The echo replies

As if lamenting:

‘O Gulf,

Giver of shells and death.

And across the sands from among its lavish gifts

The Gulf scatters fuming froth and shells

And the skeletons of miserable drowned emigrants

Who drank death forever

From the depths of the Gulf, from the ground of its silence,

And in Iraq a thousand serpents drink the nectar

From a flower the Euphrates has nourished with dew…

—from “Rainsong†(1960)

The Post Requiem for a River: Operatic Reflections on the Euphrates Appeared First on HowlRound. Visit Their Website Here.Â

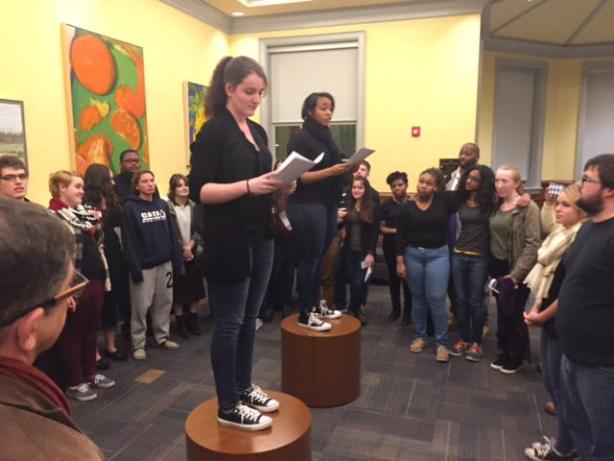

CCTA event at The Box Collective in Brooklyn, NY, 2015.

CCTA event at The Box Collective in Brooklyn, NY, 2015.

Lindsay Smiling as Gabriel York in When the Rain Stops Falling. Photo by Matt Saunders.

Lindsay Smiling as Gabriel York in When the Rain Stops Falling. Photo by Matt Saunders.

jh Samira Dainan in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie

jh Samira Dainan in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie

Samira Dainan and Mireille Bittar in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie.

Samira Dainan and Mireille Bittar in Why Yemen Matters. Photo by Jan Boeve/De Balie. Ta’ziyeh of Abbas in Ziaran, Iran 2012. Photo by Miranda Lakerveld.

Ta’ziyeh of Abbas in Ziaran, Iran 2012. Photo by Miranda Lakerveld.